The Innovation Paradox - Innovation Part 1

Why Smart Humans Didn't Change the World for 200,000 Years

I had a hard time deciding what to publish for my first Substack post.

“Write what you know”

Okay, cool advice… doesn’t help me much though.

I’ve got undergrad degrees in both history and anthropology. I spent nearly a decade lecturing on critical thinking (mostly to scientists and engineers). I worked on a theory of morality as an emergent property of self-awareness and social-awareness (only to find out Jonathan Haidt had already published something very similar).

I immigrated to Taiwan six years ago and have immersed myself in that unique culture. I’m passionate about Taiwan independence, and about correcting the flood of misinformation about Taiwan that gets propagated in otherwise decent publications, particularly in English.

In 2021 I launched a blockchain startup, was accepted into one of the leading startup accelerators… and in 2022 it failed miserably.

I currently teach grad students in business management a course on ‘Mastering the Language of AI’. Not just prompt tricks and mastery of the current tools, but rather a deep understanding of the fundamental approach we need in order to communicate effectively with AI (essential if you want to move beyond the abundant AI slop we see dominating our social media feeds).

I have somewhat diverse interests and I’ve lived long enough to pursue most of them…

Fuck it, why not just start at the beginning.

On the Origin of Our Species

I’m often frustrated by what many people treat as ‘common sense’ when it comes to evolution, intelligence, innovation, and culture.

It’s lazy, inaccurate, and usually wrapped up in nationalist and cultural mythmaking. And to be honest, it’s a lot more boring than a (hopefully) more accurate framing of history, culture, and what it means to be human.

Darwin’s theory of evolution is one of the most impactful theories in the entirety of our scientific endeavor. But we weren’t ready for it as a society when he published it, and I’m not sure we’re even ready for it now.

The biggest mistake we make when considering evolution is thinking that ‘survival of the fittest’ means survival of the strongest/smartest/best.

Fittest is relative, it’s not some absolute end, and evolution is not a linear process. Homo sapiens are not the inevitable result of natural selection driving towards an objective “best.”

It’s also not really an individual thing, evolution operates at the population scale. A trait which helps an individual survive at the expense of the local population will not be favored.

If higher intelligence harms reproductive success, then being dumber will be favored by natural selection.

What might bother me the most though, is the sort of biological determinism that leads us to believe that our success as a species, all of our innovation, is purely the product of high IQ brains.

This fundamental error extends into how we regard individuals in society, the pedestals we place them on, and the inevitable disappointment when we see how incredibly smart people can also be extremely stupid.

Challenging popular assumptions treated as axiomatic will be the topic of this series on innovation, and will be the recurring theme for this newsletter in general.

Let’s get started:

In the Beginning

We tell ourselves a wonderful myth: our big brains led naturally to innovation, which propelled us to dominate the planet. It's a neat, linear progression that puts us, modern Homo sapiens, at the triumphant end of an evolutionary march toward greatness.

The archaeological record tells a different, more surprising story: for most of human history, innovation was remarkably rare. Our intelligent ancestors spent hundreds of thousands of years barely changing their technologies at all. The same stone tool designs persisted for longer than our species has existed.

This isn't just an academic curiosity, it challenges everything we think we know about human nature and progress.

The Million-Year Toolbox: When Smart Didn't Mean Innovative

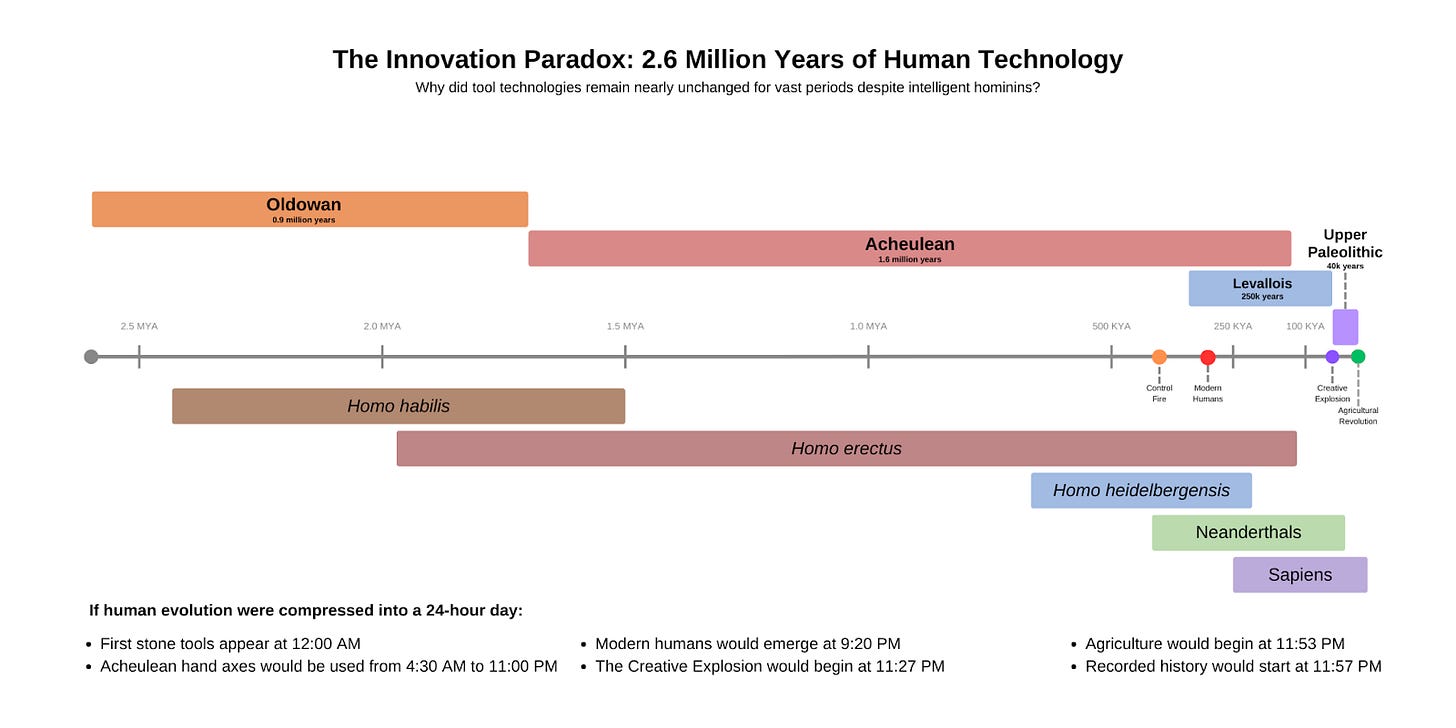

Here's a fact that should blow your mind: Homo erectus, one of our direct ancestors, used essentially the same stone tool technology (called Acheulean) for over a million years.

Let that sink in.

For context, our entire species has only existed for about 300,000 years. A million years of technological stasis would be like modern humans using the exact same technologies from now until the year 3025... and then continuing with no major changes for another 700,000 years beyond that.

This is a level of technological conservatism that's almost incomprehensible to us today.

And it's not like Homo erectus was working with a primitive brain. They had cranial capacities ranging from 850 to 1200 cc, substantially larger than earlier hominins and approaching our own average of about 1350 cc. They controlled fire (maybe), hunted cooperatively, and spread across multiple continents.

Some populations persisted until surprisingly recently, perhaps as late as ~110,000 years ago in Southeast Asia, meaning they shared the planet, if not the same landscapes, with other human species like Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens.

They were smart. But they weren't particularly innovative.

This pattern repeats throughout human evolution:

Neanderthals: Had brains as large or larger than ours, made complex tools, created art, and buried their dead, yet maintained relatively stable technologies for tens of thousands of years.

Early Homo sapiens: For the first 200,000 years of our species' existence, technological change was glacially slow. The tools used by anatomically modern humans 100,000 years ago weren't radically different from those used 200,000 years ago.

The standard narrative simply doesn't fit the evidence. Something else is going on here.

Why Your Brain Loves the Status Quo

So if it wasn't lack of intelligence holding back innovation, what was it?

Part of the answer may lie in a fundamental feature of animal psychology: novelty aversion.

Most animals, including humans, have an innate wariness toward the unfamiliar. This isn't a bug, it's a critical survival feature. In natural environments, the unknown is far more likely to kill you than benefit you. That strange plant? Probably poisonous. That unfamiliar territory? Probably contains predators or hostile competitors.

The organisms that approached novelty with caution tended to survive. The adventurous ones? They became lunch.

This isn't just speculation, we can see novelty aversion in action across the animal kingdom:

Rats avoid unfamiliar foods (a trait called "neophobia")

Most primates show strong preferences for familiar environments and social groups

Even human children display wariness of new foods and strangers

But here's where it gets interesting: intelligence doesn't necessarily reduce novelty aversion. In many ways, it amplifies it.

A smarter animal can imagine more potential dangers. It can remember more past threats. It can create more elaborate scenarios of what might go wrong. Intelligence gives you the ability to see risk everywhere, especially in the unfamiliar.

This creates a counterintuitive situation: the smarter you are, the more reasons you can generate to stick with what's worked in the past.

The Minimum Viable Novelty Principle

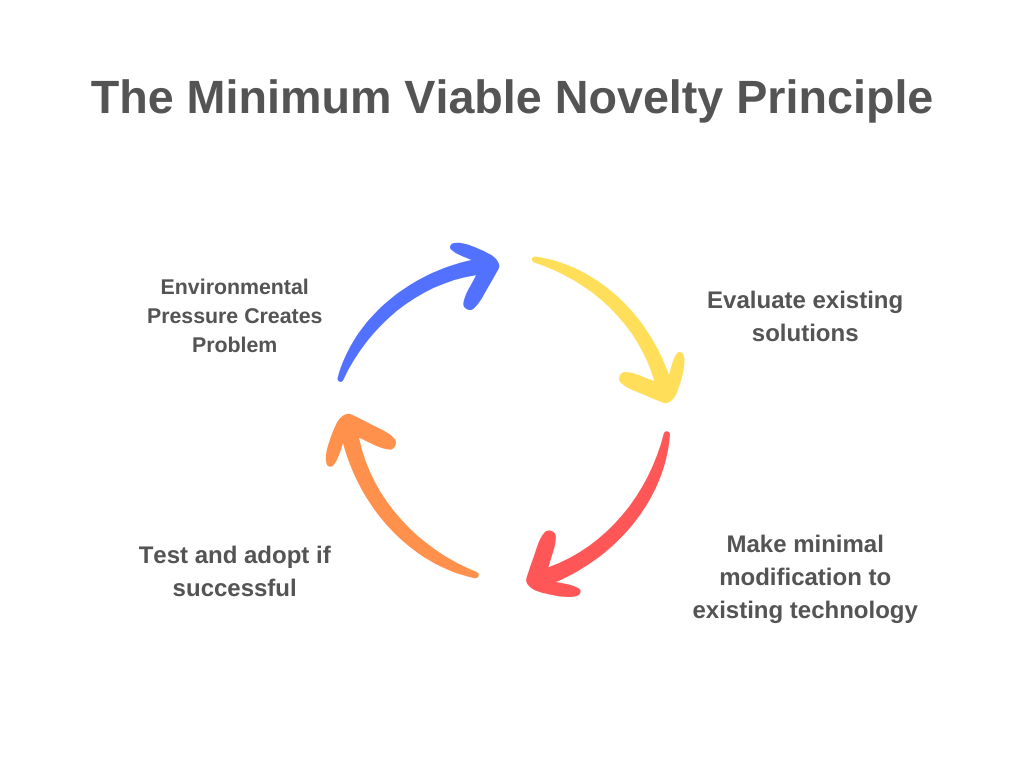

When our ancestors did innovate, they followed what I call the "minimum viable novelty" principle: they made the smallest possible changes necessary to solve immediate problems.

This isn't because they lacked creativity. It's because larger changes carried greater risks.

Consider Homo heidelbergensis, who lived roughly 700,000 to 300,000 years ago. When faced with the challenge of hunting larger game, they didn't invent entirely new weapons. Instead, they took their existing stone tools and attached them to wooden shafts, creating the first composite tools.

This was a significant innovation, but it built directly on existing technology with minimal new elements. It was the smallest viable change that solved the problem at hand.

The same pattern appears throughout human prehistory: innovation occurred primarily when:

Environmental pressures created an immediate survival threat

The innovation involved minimal deviation from existing practices

The benefits were immediate and obvious

When these conditions weren't met, our ancestors stuck with what worked, sometimes for hundreds of thousands of years.

The Neanderthal Challenge

No species challenges our assumptions about intelligence and innovation more than Neanderthals.

These weren't the brutish cavemen of popular imagination. Neanderthals had:

Brains averaging 1600 cc (larger than our average of 1350 cc)

Complex tools requiring multiple manufacturing steps

Symbolic behavior including burial practices and art

Sophisticated hunting strategies requiring planning and cooperation

Neanderthal skulls (left) were on average slightly larger than modern human skulls (right). (Credit: Weaver, Roseman & Stringer 2007 Journal of Human Evolution)

By any reasonable measure, they were at least as intelligent as early Homo sapiens. Yet their technological toolkit remained relatively stable over tens of thousands of years.

This isn't because they were "less evolved" or "primitive." It's because they were adapted to their environment, and their intelligence served to maintain that adaptation, not to constantly disrupt it.

The Neanderthal story forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: intelligence evolved primarily as a conservation mechanism, not an innovation engine. It helped us maintain and perfect existing adaptations, not constantly seek new ones.

The Revolution

So what changed? If intelligence alone doesn't drive innovation, and our fundamental brain structure hasn't changed significantly, how did we break free from hundreds of thousands of years of relative technological stasis?

The conventional story often pinpoints a dramatic shift occurring roughly 50,000 to 40,000 years ago. This period marks the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic in Eurasia and the consolidation of the Later Stone Age in parts of Africa. According to this narrative, this is when "Behavioral Modernity" – a suite of cognitive and cultural traits distinguishing modern Homo sapiens from earlier hominins and even early members of our own species – is thought to have fully emerged.

What does this "Behavioral Modernity" entail? Proponents of this view typically point to a cluster of archaeological evidence appearing around this time as markers:

Abstract Thinking & Symbolic Behavior: Manifested in the undisputed appearance of representational art (like cave paintings), personal ornaments (beads), musical instruments, and potentially more complex burial rituals.

Planning Depth: Indicated by strategies like seasonal hunting, managing resources over time, and more complex social organization.

Technological Innovation: Characterized by the proliferation of new tool types, particularly the refinement and widespread use of blade technology, and the creation of composite tools requiring multiple steps and materials.

Expanded Subsistence: Including the systematic exploitation of large game and potentially marine resources, suggesting more sophisticated hunting strategies and social coordination.

The essence of this conventional narrative is that while anatomically modern humans existed earlier, it was only around this 50-40kya timeframe that we began to think and act in fully "modern" ways, perhaps due to a final cognitive leap or cultural reorganization. This transformation, the story goes, is what truly set Homo sapiens on the path to planetary dominance.

Is this picture accurate? Did modern human behavior truly "switch on" in this fashion? In the next part of this series, we will examine the evidence behind this influential concept of Behavioral Modernity and its supposed sudden emergence.

Why This Matters Now

Understanding that innovation isn't our default setting, that we're actually wired to resist novelty, has profound implications for how we structure education, organizations, and societies today.

The same forces that kept our ancestors using the same stone tools for a million years are still at work in corporate boardrooms, government bureaucracies, and our own minds. Our natural tendency is to stick with what works, even when better alternatives might exist.

The institutions that successfully foster innovation aren't fighting against human nature, they're working with it. They create environments where calculated risk-taking is rewarded, where failure is survivable, and where the benefits of novelty are made immediate and tangible.

In a world where innovation is increasingly crucial for addressing existential challenges like climate change and the fertility crisis, understanding our deep-seated resistance to change isn't just academic curiosity, it's essential knowledge for our survival.

This is part one of a seven-part series exploring the hidden forces that shape human innovation. In part two, we'll examine how cultural systems evolved to overcome our innate novelty aversion and unleash the creative potential that had remained dormant for most of human history.