The Moral Guardrails - Innovation Part 2

How Liberty Unlocked Human Kinda-Sorta-Eventually Innovation

Alright, let's pick up where we left off in Part 1. We're wrestling with the "Innovation Paradox": Homo sapiens (and maybe earlier folks) had big brains and capable hands for hundreds of thousands of years, yet mostly... didn't invent much? Compared to the explosive change of the last few millennia, the Stone Age looks like watching paint dry in slow motion.

The big question screams at us: What finally lit the fuse? What turned us from cautious creatures of habit into the relentless, world-altering innovators we are today?

For a long time, the go-to answer was a satisfyingly dramatic story: the "Human Revolution." This idea, often called the "Later Upper Paleolithic Model," proposed a relatively sudden cognitive upgrade around 50,000 to 40,000 years ago. Sure, we looked modern long before that (anatomically modern), but according to this story, we only started thinking like modern humans (behaviorally modern) during this specific window.

What was the evidence? A seeming burst of cool new stuff showing up in the archaeological record, especially in Europe around this time: unambiguous art (think cave paintings!), fancy new blade tools, shiny personal ornaments signaling symbolic thought, signs of complex planning, and more sophisticated hunting. Compared to the older, seemingly simpler toolkits, the contrast felt stark. It demanded an explanation.

So, what flipped the switch? The usual suspects weren't slow, steady cultural improvements. Nope, the inference often leaned towards something internal and dramatic:

The Magic Mutation: Maybe one key gene variant swept through the population, suddenly boosting creativity, abstract thought, or language skills. (Remember the buzz around the FOXP2 gene? Yeah, that kinda faded).

Brain Rewiring: Less a single gene, more a significant neurological reorganization unlocking new mental superpowers.

Language 2.0: The final evolution of fully modern, symbolic language, allowing us to share complex ideas, plan elaborate projects, and pass knowledge down like never before.

Essentially, this model argued that we got a crucial hardware or software upgrade around 50kya. This cognitive leap, the story went, enabled the creative explosion, powered the "Out of Africa" expansion, and maybe helped us outcompete Neanderthals.

It’s a neat story. Compelling, even. But here's the thing: it's starting to look wrong. As archaeologists dig deeper (especially in Africa and Asia) and dating gets better, the picture gets fuzzier. Does the evidence really show a single, synchronized "revolution" caused by a sudden brain boost? Or is something else going on? Before we get to my preferred explanation (spoiler: it involves our inner moral compass), let's look at why the classic "Human Revolution" story is crumbling.

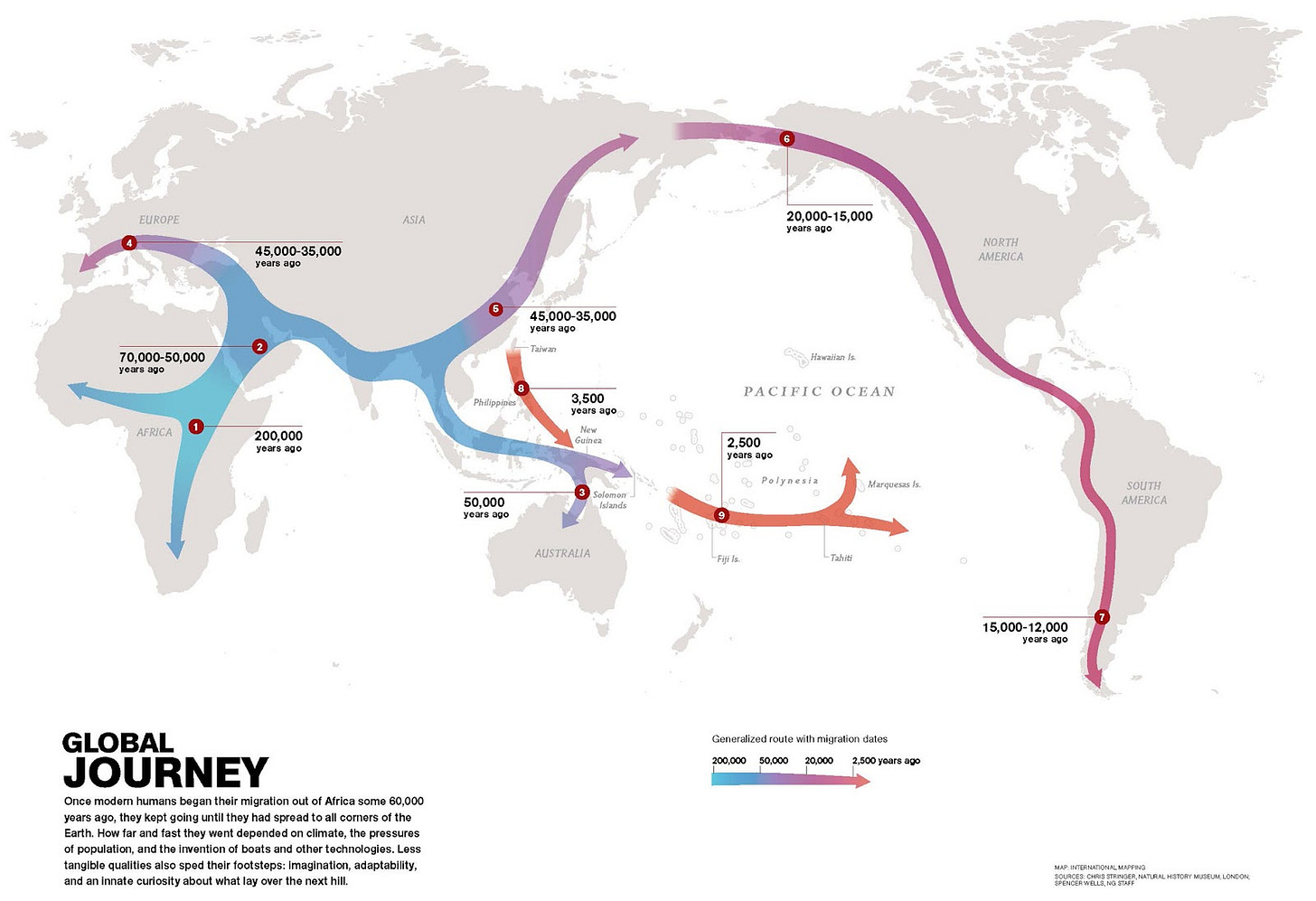

Source: National Geographic

Cracks in the Shiny "Revolution" Narrative

That idea of a sudden cognitive "Big Bang" around 50,000 years ago was tidy. It explained the cool European cave art and tools nicely. But science marches on, and the evidence piling up, particularly from Africa (where our species actually began), just doesn't fit the neat narrative anymore. The story's getting wonderfully messy.

Here’s why the "Revolution" model is shaky:

1. "Modern" Stuff is Way Older Than 50kya: Digging in Africa reveals many hallmarks of "behavioral modernity" appearing much earlier, deep in the Middle Stone Age (MSA):

Bling & Symbolism: Shell beads, indicating symbolic thought and maybe personal identity, found in Morocco date back as far as 130,000 years. Similar beads from Blombos Cave, South Africa? Around 75,000 years old.

Painting Supplies: Systematic use of ochre (pigment) pops up way before the supposed revolution. Blombos Cave even had a 100,000-year-old ochre-processing kit – basically, a prehistoric paint box.

Abstract Art?: Engraved ochre pieces from Blombos (~77-100kya) and engraved ostrich eggshells from Diepkloof (~60kya) suggest abstract design long before Lascaux.

Fancy Tech: Complex stone-tipped projectile points show up nearly 280,000 years ago in Ethiopia (Gademotta). Advanced techniques like carefully heat-treating stone to make it flake better appear by 164,000 years ago in South Africa (Pinnacle Point).

2. Not a Coordinated "Package Deal": These "modern" traits didn't arrive together in a neat bundle. Complex tools might appear in one spot long before clear art. Ornaments might pop up elsewhere without a simultaneous leap in tool tech. This piecemeal emergence doesn't smell like a single event suddenly unlocking everything.

3. Innovation Flickered, Didn't Just Climb: The path wasn't steadily upward. Researchers now talk about a "flickering" or "saw-tooth" pattern. Innovations appear, maybe stick around for a bit, but often vanish locally, only to reappear thousands of years later or somewhere else entirely. This suggests early sparks of creativity were often fragile, dependent on local conditions, not a permanent species-wide upgrade.

4. Neanderthals Complicate Things (A Lot): The plot thickens when we look at our cousins. Growing evidence suggests Neanderthals also showed signs of complex behavior once thought uniquely human. Cave art in Spain before modern humans arrived? Possible Neanderthal pigments and ornaments (like at Grotte du Renne, though debated)? Hints of burial practices? If Neanderthals could develop symbolic behaviors independently, the explanation can't just be a late, Sapiens-only "revolution." Maybe the roots run deeper.

5. Where's the Biological Smoking Gun? Despite loads of searching, no definitive "cognition gene" or clear brain change has been nailed down to the 50kya timeframe that could plausibly explain a sudden, worldwide cognitive leap.

Put it all together, and the "Human Revolution" model, while a useful starting point, looks like an oversimplification. The emergence of modern human behavior was likely longer, messier, patchier, and had roots deep in Africa, maybe even shared with other hominins. This demands a different kind of explanation – one that accounts for both the incredibly long stasis and the eventual, flickering start of innovation. To get there, I think we need to look inside ourselves, at the very structure of human morality.

Alternatives: Demographics, Environment... But Is That Enough?

Okay, so the simple "Revolution" model is shaky. What else could explain things? If it wasn't a sudden brain upgrade, what accounts for the long freeze followed by the patchy, flickering thaw of innovation? Smart people have proposed several alternatives, shifting focus from biology to broader processes:

1. It's the Network, Stupid! (Gradual Culture & Demographics): This is probably the leading alternative view, championed by folks like Sally McBrearty and Alison Brooks. They argue anatomically modern humans likely had the potential for complex behavior much earlier. The bottleneck wasn't brainpower, but the sheer difficulty of inventing, keeping, and passing on complex skills in small, isolated groups.

Think about it: making intricate tools, remembering rituals, developing complex hunting plans – these things are hard to figure out and super easy to lose if the few people who know them die off. Imagine trying to maintain Wikipedia with just a handful of users scattered across a continent, constantly facing floods and famines. Innovations might have constantly "flickered" into existence, but couldn't stick.

The key insight here is demography. According to this view, championed computationally by researchers like Adam Powell, only when human populations grew larger, denser, and better connected did they cross a threshold. More people = more potential inventors + better buffers against knowledge loss + faster spread of good ideas. This creates a "cultural ratchet effect" – like using Lego bricks, you can reliably build on previous advances instead of starting over. This matches the "saw-tooth" pattern pretty well – the appearance of complexity tracks population density.

2. Mother Nature Made Us Do It (Environmental Pressure): Another factor is environmental change. Shifting climates, scarce resources, or the challenges of moving into new environments could have spurred innovation out of necessity. Adapt or die! Groups that could tweak their tools, strategies, or social structures in response to pressure had an edge. While maybe not explaining art directly, environmental stress could definitely accelerate the rate of change.

3. Deeper Roots & Multiple Actors: As mentioned, evidence for Neanderthal complexity (and perhaps others) suggests the foundations for "modern" behavior might pre-date the split between our lineages. If so, we should be looking for shared ancestral potentials, not just uniquely Sapiens magic. Researchers like Francesco d'Errico and João Zilhão strongly advocate this view.

These alternatives – demographics, cultural learning, environment, deeper roots – are valuable. They align better with the messy archaeological reality than the old "Revolution" story. They help explain how innovations, once sparked, could finally stick and spread.

But... do they fully capture the human element?

Is it really just as simple as the lack of a network? Were we, and our hominid relatives, always innovating and there just wasn’t a strong enough network to make sure those innovations stuck around?

Maybe, but when we look at innovation in recorded history, it feels like something else is missing. We do see marked periods of conservatism, a resistance to change. It seems like that conservatism is deeply rooted in our species, and therefore maybe we should look a bit deeper at our internal psychological motivations and how those relate to innovation.

To explore that layer, let's dive into our evolved moral operating system.

A Deeper Engine: The Psychology of Sticking to Your Guns

Demographics and environment help explain how innovation could persist. But they don't fully get at the why – why was innovation seemingly suppressed for hundreds of thousands of years? To understand that deep-seated conservatism, and what it took to overcome it, we need to look at the software running human social life: our evolved moral psychology.

A fantastic tool for this is Moral Foundations Theory (MFT), developed by Jonathan Haidt and colleagues. MFT suggests our moral judgments aren't just logical deductions; they spring from innate, evolved psychological systems – 'foundations' – built to solve ancient social problems. Haidt initially proposed five core foundations found across cultures:

Care/Harm: Sensitivity to suffering, nurturing the vulnerable. Essential for raising helpless kids and keeping friends.

Fairness/Cheating: Focus on justice, rights, reciprocity. Helps manage cooperation – you scratch my back, I scratch yours.

Loyalty/Betrayal: Underpins group cohesion, patriotism, self-sacrifice for "us." Vital for forming strong, competitive teams.

Authority/Subversion: Respect for tradition, legitimate leaders, social order. Keeps hierarchies stable and transmits knowledge across generations.

Sanctity/Degradation: Focus on purity, avoiding contaminants (physical or symbolic), disgust. Likely evolved from avoiding pathogens but extends to moral disgust and revering sacred things/ideas.

Now, here’s the kicker for the Innovation Paradox: Most of these foundations, in their default mode, are profoundly conservative. Their job is to maintain stability, preserve what works, manage risk, and keep the group together. They were evolution's risk-management toolkit, designed to keep societies safely on the path of proven tradition. They weren't trying to stop innovation, but their combined effect was a powerful brake on radical change.

Think how this played out:

Sanctity: A powerful shield against the unknown. No germ theory? Strong disgust reactions and food taboos are life-savers. This likely bled into how things were done. Why barely change hand-axe designs for a million years? Maybe making them differently felt viscerally wrong, unclean, disrespectful of the 'proper' way.

Authority: Ensures vital survival knowledge isn't lost. An elder shows you the right way to track an animal or knap flint – you listen, you copy meticulously. Essential for passing down knowledge, but fundamentally backward-looking. Challenging the elder wasn't just rude; it could be fatal.

Loyalty: Built strong "us vs. them" bonds for cooperation and defense. The downside? Deep suspicion of outsiders and their weird, potentially dangerous ideas. Conformity was king.

Fairness: Kept cooperation humming but likely reinforced existing patterns. Big changes upsetting the established balance of who does what and gets what would be met with skepticism unless the payoff was immediate and obvious to everyone.

Care: Focused on protecting the vulnerable, which also meant discouraging risky new ventures that could endanger kids or the group's safety net.

This psychologically ingrained conservatism, rooted in our gut feelings about right and wrong, provides a compelling explanation for the Innovation Paradox. For ages, this powerful suite of moral instincts acted like gravity, constantly pulling behavior back towards the established norm. Trying something genuinely new wasn't just impractical; it likely felt wrong, risky, disloyal, disrespectful, maybe even disgusting. Overcoming that required more than just a clever idea. It required a counter-force within our own moral psychology.

The Counterbalance: Enter Liberty/Oppression

So, if the first five foundations (Care, Fairness, Loyalty, Authority, Sanctity) built such effective walls against rapid change, how did we ever break out? What force could possibly push back against this deep-seated drive for stability?

The answer, proposed within the expanded MFT framework, is a sixth foundation: Liberty/Oppression.

Haidt and his team identified this later. The Liberty foundation is our built-in sensitivity to domination, coercion, and bullies. It's that feeling you get when someone tries to control you unfairly. It fuels our desire for autonomy, for freedom, for being our own boss. Think of it as the persistent "inner toddler" who hates being told "because I said so" and instinctively pushes back against constraints.

Unlike the other five, which mostly focus on group cohesion or stability, Liberty is inherently individualistic and challenges the status quo. Authority says "Respect the hierarchy." Loyalty says "Fit in with the group." Liberty says "Yeah, but why?" It's the voice asking, "Why do they get to decide?" or "Why can't we do things differently?"

Liberty doesn't erase the other foundations. We still care about group harmony, fairness, tradition, etc. But it injects a crucial counterbalancing tension into our moral minds. It provides the motivation to:

Resist bossy or arbitrary Authority.

Question stifling group norms (pushing back against Loyalty's pressure to conform).

Explore beyond the boundaries set by fear or tradition (poking at Sanctity's taboos).

Crucially, Liberty doesn't need to be "stronger" than the others all the time. It just needs to be present enough to create friction, to spark questions, to make some individuals restless enough to try something new.

The emergence, or perhaps the increasing expression and influence, of this Liberty foundation, especially when combined with the right demographic conditions (bigger, connected groups), looks like the missing psychological catalyst. It's the ingredient that could start rewiring our ancient moral machinery from a system purely focused on preserving the past into one capable – however reluctantly – of driving innovation. How this cosmic tug-of-war played out is next.

The Synthesis: How Liberty + People = Innovation (Eventually)

Introducing Liberty gives us the missing psychological ingredient. But innovation didn't just magically ignite. The real story is likely a slow, uneven shift in the balance of power between Liberty and the more conservative foundations (Authority, Loyalty, Sanctity), heavily influenced by social context – especially how many people were around and how connected they were. It wasn't Liberty replacing the others, but gaining enough clout, under the right conditions, to change how the whole system worked.

This "dynamic balance" view, integrating moral psychology with demographics, actually explains the puzzling archaeological patterns much better than the old "Revolution" model:

1. Turning Brakes into Engines (Sometimes):

When Liberty gains traction, especially in larger, more connected groups, it doesn't just fight the old guardrails; it can subtly transform how they operate regarding new ideas:

Authority: From Rigid Rules to Flexible Wisdom: Pure Authority demands strict adherence ("Do it this way!"). Authority tempered by Liberty can become more adaptable. Respect might shift towards skilled innovators, not just elders. Tradition is valued, but not blindly followed ("Okay, the old way works, but your new spear point technique looks promising..."). Maybe those Upper Paleolithic burials showing status based on skill reflect this?

Loyalty: From Tiny Tribes to Vast Networks: Unchecked Loyalty means distrusting outsiders. Liberty encourages exploration and interaction. Trust networks expand, letting ideas and resources flow between groups. Bingo: you get the long-distance trade networks we see emerging archaeologically (seashells, tools, amber moving hundreds of miles). These weren't just markets; they were knowledge highways, accelerating innovation by connecting diverse minds – a prehistoric open-source movement, nudged along by Liberty overriding pure suspicion.

Sanctity: From Universal Taboos to Selective Sacredness: Pure Sanctity makes huge areas off-limits ("Don't touch that! It's sacred!"). Liberty pushes boundaries, forcing Sanctity to become more focused. Societies might keep strong rituals around core beliefs (death, spirits) but allow tinkering in practical areas (tools, food). This selective sacralization – knowing what not to mess with versus what can be explored – is vital. It allows exploration without total chaos, explaining why innovation often appears domain-specific.

2. Making Sense of the Messy Archaeology:

This model fits the evidence better:

Early & Flickering Sparks: Explains why cool stuff appeared early but didn't immediately spread. The potential (Liberty impulse + brainpower) existed, but the dominant cultural balance (conservatism) or demographics (small, isolated groups) often snuffed out novelty. Sparks flew but fizzled.

Things Arriving Separately: Makes sense because different innovations challenge different foundations. Changing tool design might hit less resistance than changing burial rites. The "package" wasn't delivered together because the psychological hurdles varied.

Different Strokes for Different Folks (Regional Variation): Why different patterns in Africa, Europe, Asia? Local environments, populations, and cultures created different starting MFT balances and demographic paths, leading to diverse innovation journeys – the "complex mosaic" researchers talk about.

The Ignition Point: Sustained innovation finally took off when and where societies hit a 'sweet spot': enough Liberty expression to consistently challenge conservatism, plus the population density and connections needed to maintain, share, and build upon new ideas instead of losing them.

3. Working With Demographic Models:

This psychological view doesn't replace demographic explanations; it completes them. Demographics explain how ideas persist and spread (the network effect). MFT/Liberty helps explain the generation of new ideas (overcoming inertia) and the receptiveness to them. Together, they paint a richer picture: psychological potential (MFT balance) interacting with social structure (population) shapes innovation's path.

Consider this nuance: Maybe Liberty's roots are ancient (think Homo erectus exploring), but Homo sapiens' advanced symbolic thought amplified both Liberty's expression (art, planning) and the power of conservative foundations, especially Sanctity (via complex rituals, taboos). Our species' initial conservatism might not stem from lacking Liberty, but from having uniquely powerful symbolic guardrails. Overcoming that took tens of thousands of years, needing the right cultural and demographic shifts for Liberty to finally gain leverage.

Looking at early innovation through this lens – a messy, conflicted interplay between our evolved moral instincts and our social world – feels much more realistic than neat stories of sudden revolutions. It reveals our ancestors wrestling with the same basic tensions between stability and change, tradition and exploration, that drive our world today.

Managing Fear: Sanctity, the Double-Edged Sword

Okay, so far Sanctity (purity, taboo, avoiding the 'icky' unknown) looks purely like an anti-innovation force, a wall Liberty has to smash. But it's more twisted, and more interesting, than that. Sometimes, Sanctity doesn't just block change; paradoxically, it can enable the risky ventures Liberty prompts.

How? By helping us cope with the crushing anxiety of uncertainty.

Think about traditional fishing crews, like anthropologists often describe. Before heading into the dangerous, unpredictable ocean, they often perform rituals, say prayers, follow specific taboos. Why? It's not just magical thinking. Fishing is profoundly uncertain. Skill and tech help, but storms happen, fish disappear - much is totally out of their control.

The ritual doesn't change the ocean. But it does something vital psychologically: it makes the uncertainty bearable. It imposes a sense of order, predictability, and maybe perceived control onto chaos. It lowers anxiety, freeing up mental energy to focus on what can be controlled (mending nets, steering the boat). It's like prehistoric Xanax – a coping mechanism letting necessary but scary ventures proceed without being paralyzed by "what ifs."

This reveals a fascinating dance between Sanctity and Liberty. When Liberty pushes us towards something new and inherently risky – exploring uncharted territory, trying a radically new farming method, launching a crazy startup – the sheer anxiety can be paralyzing. Sanctity-based rituals, shared beliefs, and structured practices can provide the psychological scaffolding needed to tolerate that fear and move forward. The shared ritual offers comfort, reinforces group commitment, and provides a handle on the unknown, allowing a Liberty-driven leap that pure rational risk calculation might forbid.

But here's the deadly twist: Sanctity is a double-edged sword. While it can enable risk by managing anxiety, it can also shut innovation down completely by declaring certain things 'sacred' and utterly off-limits. Questioning the sacred doesn't just feel wrong; it triggers visceral disgust or outrage. It's a violation.

This dynamic helps explain why innovation is often so uneven, even within the same society or company. Areas protected by strong Sanctity intuitions – core religious dogmas, sacred national myths, the company's "founding story," deeply ingrained "this is how we do things" processes – stay stubbornly conservative. Questioning them is taboo. Meanwhile, less 'sacred' domains become arenas for experimentation driven by Liberty and practical needs.

The most innovative cultures or organizations, then, aren't necessarily ones that ditch Sanctity entirely (they might become anxious, anchorless wrecks). Instead, they often figure out how to channel Sanctity productively. They use shared values, mission statements, even rituals to manage the anxiety of exploration, while being very careful about what they don't allow to become so sacred it can't be questioned or improved. Finding that balance – using Sanctity for resilience without letting it strangle Liberty – is the perpetual tightrope walk for progress.

Understanding this complex dance between pushing boundaries (Liberty) and managing the fear (Sanctity) changes how we see history. For example, simply stating "Religion always stifled science" misses the point. Institutions often simultaneously shut down inquiry in sacred areas while actively funding innovation in others they deemed okay – a direct result of this psychological balancing act we'll explore more later.

Conclusion: The Universal Spark, The Uneven Flames

So, we've journeyed from the simplistic "Human Revolution" idea to a richer, more complex picture. The archaeological record suggests a gradual, patchy emergence of "modern" behavior, not a sudden event. I've argued the key lies not in a biological leap, but in the shifting balance of our evolved moral psychology: the constant tension between conservative forces (Authority, Loyalty, Sanctity) and the disruptive impulse of Liberty, all critically enabled (or disabled) by demographics.

Innovation wasn't a gift suddenly bestowed upon us. The potential was likely always simmering. Its expression was unlocked as Liberty gained enough leverage within growing, more connected human networks to nudge, transform, and sometimes bypass the powerful psychological guardrails favouring stability. Sanctity played a complex role, sometimes managing the fear of the new, sometimes blocking it entirely.

Why dredge up the moral psychology of Ice Age hunters? Because the exact same dynamics are running the show right now. This tension isn't ancient history; it's the humming engine beneath modern life:

Tech Disruption: Think AI, crypto, green energy. Liberty-driven innovators crash against established industries and norms defended by Authority ("experts say...") and Sanctity ("our traditional way of life!"). Resistance is often gut-level moral reaction, not just economics.

Political Gridlock: So many modern fights (immigration, social issues, free speech) map onto clashes between groups emphasizing Loyalty/Authority/Sanctity versus those prioritizing Liberty/Care or different takes on Fairness. Understanding the MFT roots reveals the deeper currents beneath the arguments.

Business Innovation Woes: The "innovator's dilemma" is this tension played out in boardrooms. How do you keep the core business stable (Authority/Loyalty/Sanctity around "how we do things") while fostering the radical change needed to survive (Liberty)? Companies often fail because their psychological immune system attacks novelty.

Your Own Life: Ever felt the pull between trying something new (a job, a city, a relationship) and the comfort of routine or fear of the unknown? That's Liberty versus the conservative foundations (often managed by your own personal 'rituals' and comfort zones, echoing Sanctity).

This deep history shows progress isn't automatic. It emerges from a fragile, often conflicted, psychological balancing act, amplified or choked by our social structures.

But this raises the next giant question. If this psychological toolkit, this MFT tug-of-war, is a human universal, why do standard histories of Big Breakthroughs always seem to zoom in on specific times and places?

After the deep past, the spotlight swings almost inevitably to Ancient Greece – its philosophy, math, democracy depicted as a unique explosion. Then it jumps to Renaissance and Enlightenment Europe, painting the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions as the moments that supposedly put the West on a unique path to modernity.

These narratives imply something fundamentally different happened there. Unique genius? Pure reason discovered? Better institutions? What supposedly allowed these societies to ignite and fan the flames of innovation far brighter than others?

Unpacking that puzzle – interrogating the standard stories about these golden ages and asking if they hold up – is where we're headed next. Join me as we start digging into these celebrated eras and the conventional reasons given for their success.

This is part two of a seven-part series exploring the hidden forces that shape human innovation. In part one, we examined why intelligence alone doesn't drive innovation. In part three, we'll begin investigating how different cultures navigated the balance between Liberty and the other moral foundations, starting with the usual suspects.